The military funded this tech to help soldiers use words rather than weapons. But it turns out that your heart rate says a lot about your response to ads.

In 2005, neuroscientist Paul Zak was on an airplane, hunkered down on his laptop in hopes of finishing his work before he arrived home to his wife and kids.

Turbulence hit, shaking his laptop so fiercely he could no longer type. So he did what anyone would do. He turned on a movie—Million Dollar Baby, which had just won the Oscar for best picture.

By the end of the movie, Zak’s seat partner was poking him in the arm, asking him if he was okay. “Gobs of goop were coming out of every orifice in my face.”

The gut-wrenching father-daughter tale had shaken him to his core.

When Zak returned to his lab the next day, he told a psychologist in his lab about his strange reaction. The psychologist wasn’t surprised. “Well, yeah, psychologists use video all the time to change people’s moods.”

Zak wanted to learn more. Researchers on his team had been researching what promotes and inhibits the release of oxytocin, the empathy neurochemical in the brain known to foster human connection. Until then, they’d been studying what happens when humans interact with each other. But what if they could foster it at a distance through video, and quantify the effect that different kinds of content had on human connection?

THE ENGAGEMENT PARADOX

Go to any advertising conference, and you’ll hear the word “engagement” bandied about more than any other buzzword. It’s easy to talk about, but much harder to quantify. Metrics like page views, impressions, views, and shares are very rough proxies for affinity. Even surveys and focus groups that ask consumers if they like an ad, or if it influenced their purchase decision, don’t reliably capture its true effect.

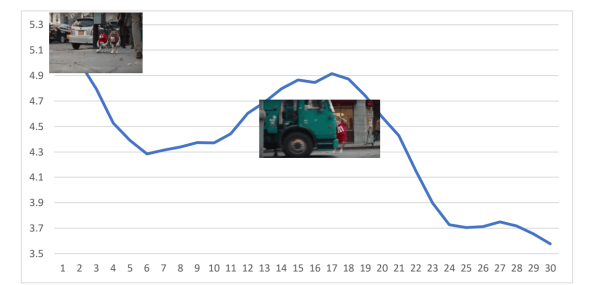

But after 12 years of research, Zak’s team at Immersion Neuroscience is hoping to change that. It’s launching a sensor that measures people’s immersion in video content and live experiences—from keynote speeches to shopping experiences—via a small wearable that straps onto the forearm.The wearable and its accompanying software, called the Immersion Neuroscience Platform, use heart rate to measure the production of oxytocin, the empathy drug associated with human connection. This reaction is quantified through Immersion Neuroscience’s Immersion Quotient (InQ) algorithm that runs on a 0-10 scale and is able to predict purchase actions after brand experiences with a 75% to 95% accuracy, according to Zak. Better yet, he claims, anyone can learn to use the wearable and its accompanying software in just 30 minutes. And monitoring just 35 people provides statistically significant results.

If Zak’s claims pan out as the technology is more widely deployed–and if consumers don’t get spooked by the prospect of feeding their anonymized heart rate into a database for commercial purposes–it’s a potential game changer for the advertising world.

Of course, if taken to the extreme, this sort of monitoring also sounds like something that could be part of a Black Mirror plotline. Or it could become a universal technology that helps humans understand themselves and their interests in a much deeper way, greatly improving the way we live and learn.

Its back story lends itself to some kind of mythology. The project received early funding from the Narrative Networks project of the U.S. military’s Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), which was looking for ways to improve military effectiveness by training soldiers to use words instead of weapons to reduce conflict around the world.

The idea was the same as with ad testing; the military could test the effect that different persuasion techniques and narratives had on villagers in Afghanistan, who were the key to figuring out where the Taliban was hiding.

The experiments were successful, leading the researchers to spin off the technology into a potentially lucrative commercial application.

NEUROSCIENCE IN ACTION

While the potential applications of the Immersion Neuroscience Platform are vast, the soft launch of the application with a half-dozen brand partners is focusing on two primary applications: ad testing and corporate training.

For ad testing, the tracker offers something of a holy grail. What if advertisers actually knew how ads or social videos would affect consumers’ unconscious and emotional mind before investing millions of dollars in their production or distribution?

Zak claims that this would be a huge upgrade over the old-school way of doing things. A decade of research by his team has found that being immersed in an ad is much more likely to correspond with purchase action than merely saying that you like it. Many times, people who say that they like an ad aren’t actually immersed in it—and vice versa.

Take this year’s Super Bowl ads. Diet Coke’s “Groove” ad came in dead last in USA Today‘s AdMeter rankings, which asks viewers which ad they liked the most. But when Zak measured the brain responses of eight participants while they watched the game’s commercials in random order, Diet Coke’s ad had the highest immersion rate—by far.

Diet Coke’s agency, Anomaly, likely got lambasted after USA Today‘s rankings came out, but the spot may have had a much stronger effect than anyone realized.

Conversely, the top-rated ad, the NFL’s “Touchdown Celebrations to Come,” came in 11th in Zak’s rankings.

While such a small sample size begs healthy skepticism, Zak’s explanation for the gap makes a lot of sense. “Groove” has a much more interesting story than “Touchdown Celebrations to Come,” which is essentially just a disjointed celebrity montage.

As he explains:

Her story about Diet Coke Twisted Mango continues as she starts to dance and talk about how great the product makes her feel. Then, the dancing gets faster and weirder. Viewers are intrigued and can’t look away. Just before the peak at 22 seconds, she says, ‘Maybe slowing it down, maybe it’s getting sexier.’ The video is shot asymmetrically with the actress staying on the one side of the frame for most of the commercial, also an oddity that holds our attention. Importantly, the story that the actress is telling features the product and is the reason she is dancing. There is a narrative arc we can follow: if we want to be happier and perhaps sexier, we should drink Diet Coke Twisted Mango.

Compelling story arcs are the key ingredient in ads that trigger high levels of immersion in our brain. As my coauthor Shane Snow and I write in our just-released book, The Storytelling Edge, the past two decades of neuroscience research has shown that our brains are addicted to stories; our synapses light up when we hear good stories, illuminating the city of our mind.

“You’ve got to build tension,” Zak explains. “When we break that data down, second by second, when an ad starts, the first thing is that you’ve got to capture my attention, say with a hot open just something that’s mysterious or unusual or odd. Once you have my attention, you’ve got to do something with it. The ‘do something’ is make me care about it. You make me care about it by having some human conflict or drama.”

The use of neurosensors to test ads could also allow brands to optimize their spots in compelling ways. Take the second-most immersive Super Bowl ad in Zak’s study, M&M’s’ “Human.” It has two peaks: At the start, when the viewer sees two M&Ms walking around New York, with Red saying, “I’ve had three people try to eat me today.” This indicates the power of establishing tension early in a spot.

The second immersion peak comes at 18 seconds, when Danny DeVito shouts “no one wants to eat me” and promptly gets hit by a truck. Engagement with the ad then plummets. If the ad had been tested, M&Ms and BBDO likely could have cut the spot to 15 seconds and saved $2.5 million per Super Bowl ad buy.

TELL ME WHAT I REALLY LIKE

The second application of the Immersion Neuroscience Platform, while less sexy, could have huge ramifications for the corporate world as well. Corporations spend millions of dollars each year on corporate trainings or large-scale conferences like Dreamforce without really knowing how engaging the sessions actually are, other than participant surveys.

Zak believes that his platform can successfully quantify how engaged people are with certain sessions, and then make recommendations for what they should do next.

“Let’s suppose you go to a three-day corporate event, and on day one, you’re wearing our sensor and it measures immersion in a bunch of different sessions you went to,” he explains. “There are parallel sessions, so you have some choice. And then we can recommend what you might want to do on day two and day three, based on what you did on day one.”

Zak’s team tested this use case at a major global conference in Houston last year and unearthed some intriguing findings. Short, high-energy talks performed best. Hour-long talks required a strong narrative arc, or else attention fell off. And the brain loves variations, meaning that multimedia-heavy presentations were most engaging.

IS THE WORLD READY?

For Zak, the potential applications of his technology are endless. Politicians, for instance, could use it to live-track and optimize how they were resonating with different demographics of constituents in debates, and change their approach mid-stream accordingly. (Zak’s focus groups, in fact, did find that Trump was by far the most immersive candidate during the Republican debates, and that Hillary Clinton scored a zero emotional connection during one closing argument in a debate with Bernie Sanders.)

Even more ambitiously, the neurosensor could be used as the ultimate taste algorithm, revealing what parts of our life and learning experiences immerse us the most. We could see what education techniques work best for us, which work environments make us more productive, and even which recreational activities we truly enjoy.

But are people actually ready to hand over this kind of intimate data about their brains?

We worried about that in the beginning,” admits Zak. “But at all the events we’ve been to, we say, ‘Look, we’ve got 30 of these sensors, who’d like to wear them?” All the hands go up. People think it’s pretty cool. Again, the data are anonymized, they’re mixed in with everyone else’s data, so we don’t know anything about you personally. We’re not getting any names.”

Since just 35 people will yield statistically significant results, Zak doesn’t foresee any issues in the opt-in approach. “We’re not using the data in any way that’s creepy or somehow manipulative or anything like that,” he adds.

The fact that Zak’s intentions and implementation are honorable doesn’t ensure that technology along these lines will always be used for good. But the more immediate question is whether his promise of democratized neuroscience for the marketing world will help marketers achieve their ultimate goal: selling more stuff.