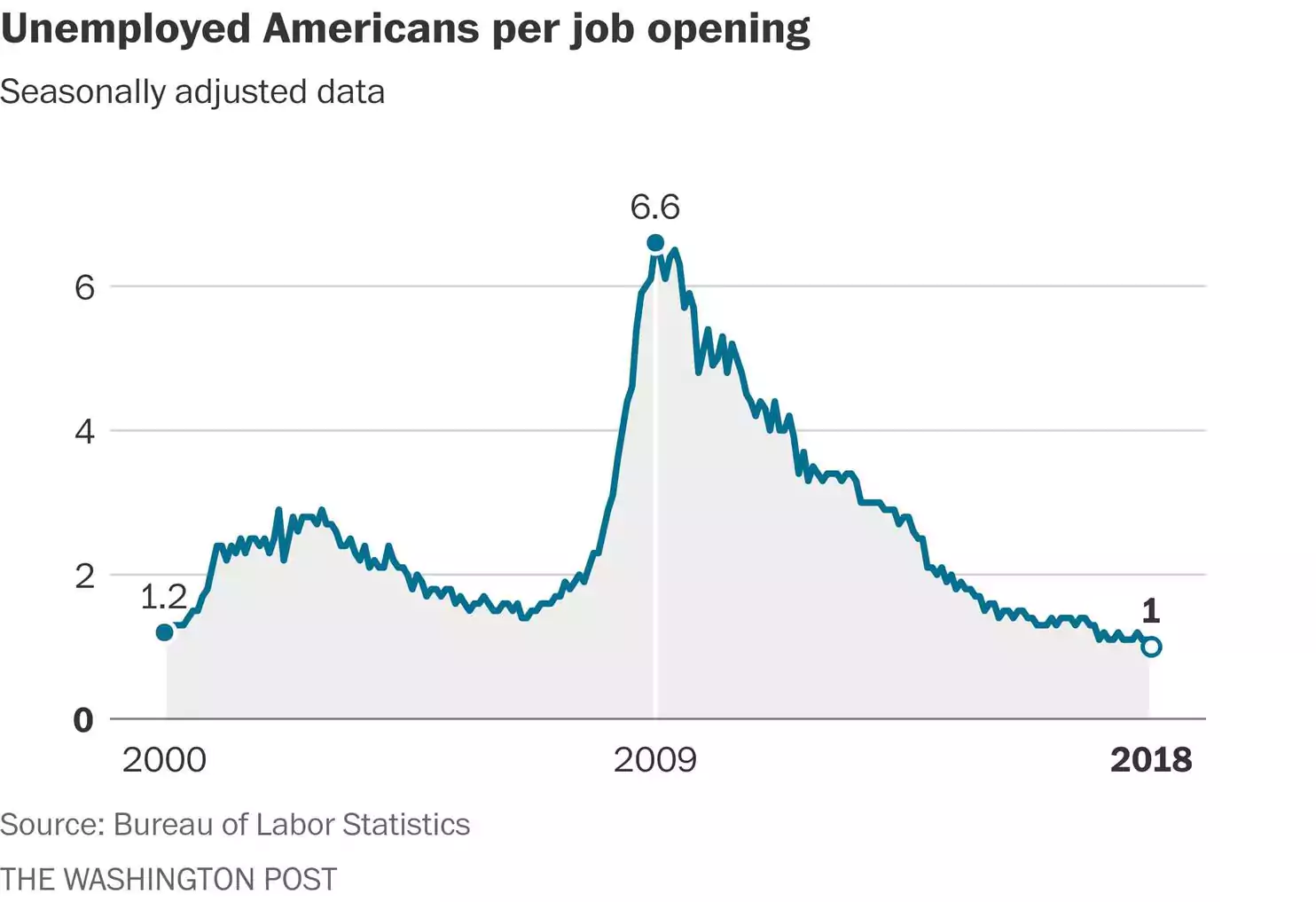

The United States now has a job opening for every unemployed person in the country, a sign of just how far the nation has turned around from the recession that cost so many Americans their jobs nearly a decade ago.

The Labor Department reported Tuesday there were 6.6 million job openings in March, a record high — and enough for the 6.6 million Americans who were actively looking for a job that month.

“The labor market is literally on fire it is so hot with job openings,” said Chris Rupkey, chief financial economist at MUFG Union Bank.

March marked the first time there has been a job opening for every unemployed person since the Labor Department began keeping track of job openings in 2000. White-collar businesses, construction and warehouses all expanded their recruiting in March, the Labor Department reported.

It’s likely that the United States will soon be in a situation where there are more job openings than job seekers. Rupkey points out that the number of unemployed Americans fell to 6.4 million in April.

Many businesses executives say their top worry is that they can’t find enough workers. Unemployment is at the lowest level in nearly two decades, and the jobless rate for African Americans and Hispanic Americans is at an all-time low. Companies are revising their hiring practices to ensure that they do not rule out any potential good workers, especially those who might not have a college degree or people who have criminal histories and have served time in jail.

Theoretically, everyone who wants a job should be able to get one now, but that’s not what typically happens, even in good economic times. In a nation as big as the United States, there will always be people who quit their jobs and take time to find new employment. (More than 3 million people voluntarily left their jobs in March, according to the Labor Department.)

There is also somewhat of a mismatch between job seekers and job openings. The people looking for work don’t always have the right skills or live in a place where there are a lot of opportunities to get hired.

“No one is hiring. They are creating jobs, but they aren’t filing them,” said Diane Swonk, chief economist at Grant Thornton. “There is clearly a gap in skills.”

Companies have two options these days, many economists say: They can pay more for talent; or they can expand their training programs. So far, there have been a lot of anecdotes of firms taking these actions, but it’s not showing up yet in the nationwide data.

Wage growth is stuck at a lackluster level. In the past year, wages grew 2.6 percent, a historically low rate, according to Labor Department data released Friday. Although there’s been a noticeable increase in hiring bonuses with some blue-collar jobs like trucking and railroad work paying up to $25,000, those are one-time payments, not true pay raises.

In Washington, the Trump administration is pushing companies to add more apprenticeships, and in states such as Rhode Island and Tennessee, state lawmakers have made community college free in an effort to make it easier for workers to beef up their skills and résumés. (Maryland just approved it).

“Training workers is expensive. It’s not something we’ve done in a long time in America,” Swonk said.

The classic economic explanation for why wages aren’t rising is that the United States’ worker productivity has been low since the Great Recession. Productivity is a measure of how much output each worker does per hour. When that rises, wages typically follow. A goal of President Trump’s tax cuts is to get companies to invest more in new technologies and factories in the hope of lifting productivity and, in turn, wages. It’s too early to tell whether that’s happening.

Another popular theory for why companies are keeping wages low is that there are more people looking for work than the Labor Department statistics imply. They say there are lots of people “on the sidelines,” especially men in their prime working years, who aren’t working for reasons that aren’t fully understood. As the economy continues to add jobs, some Americans who had given up looking for work are starting to search again. There are also Americans who are underemployed: They have a job now but want a full-time role.

“It’s worth remembering that 5 million [people] are still working part time but would like full-time work,” said Mark Hamrick, senior economist analyst at Bankrate.

Walmart, for example, opted to give more hours to its part-time employees instead of hiring additional workers this past holiday season.

As the job market continues to tighten, economists keep predicting this is the year that wages will finally start to rise for most Americans. But some researchers are starting to point to deeper issues that could be holding wages back, such as rising health-care costs that force employers to put money toward health expenses that would have gone to wage increases. Or the fact that many small and midsize cities are now dominated by a few companies. Those power player firms act as the “pace cars” for wages in the area. If they go low, everyone else follows.

There’s no consensus on what’s holding wage hikes back, especially as conditions appear to be ideal for workers to finally get substantial raises.