by Joe Passov

Source: thengfq.com, May 2019

“In a eulogy,” award-winning architect Tom Doak once stated, “there is always a tendency to dismiss the weaknesses of the departed and canonize him for the most basic of human qualities. I suppose the same is true for golf courses, especially since their mortality is not preordained…”

No good golf course deserves to die, though many do—and for many reasons. Course closures have outweighed new openings for 13 straight years during the ongoing balancing of supply and demand in the U.S. golf market, and Doak himself is a notable victim. No fewer than six of his course designs have closed in the past eleven years, a surprising number considering his remarkable successes. Most hurtful is the 2008 demise of High Pointe in Williamsburg, Michigan, his first solo design and a former member of America’s Top 100 courses.

Overall, 198.5 courses closed throughout the U.S. last year, as measured in 18-hole equivalents. Nevertheless, the shuttering of a popular or once-popular golf course isn’t necessarily all bad. It’s typically not celebrated, but the reality is that not every golf course is destined to live forever. In some cases, a golf course served its purpose and its remnants will reward its users equally well, or even better.

A strong example is the recent turn of another Midwestern property, Tam O’Shanter Golf Course in Canton, Ohio. The 36-hole public-access facility closed in November 2018 after a 90-year run during which it hosted the Ohio Open from 1989-2001 (an event whose past champions include Jack Nicklaus, Byron Nelson and Tom Weiskopf) and the USGA’s 1994 U.S. Women’s Amateur Public Links.

For Tam O’Shanter owner Chuck Bennell, great-grandson of one of the course co-founders, the decision was simple.

“I was 75, there was no ‘family successor,’ and the real estate was worth more than our golf course business,” said Bennell, a longtime NGF member. “It had been clear to me for at least ten years that our business strategy needed to focus on an exit plan.”

After 90 years, the last round of golf at Tam O’Shanter in Ohio was played in November of 2018. (Photo: CantonRep.com / Ray Stewart)

Tam O’Shanter had been profitable, Bennell explained, thanks to the happy accident of being in business for 90 years (and therefore debt-free), and to the non-accident of having very capable managers and a dedicated team of seasonal workers. On the other hand, over nine decades ownership had spread among 20 people all over the country who were third and fourth generation members of the two families that founded the course.

“None of those owners relied on income from the company to buy groceries and I was the only person in the ownership group with golf operations experience,” said Bennell. “It was the right time to leave the golf business.”

So why not sell to someone who wanted to keep alive the golf operation? “Not a single local investor or investment group stepped up to say ‘We’d like to buy this as a golf business,’ said Bennell. “Not a single one.”

Tammy, as it was known by locals, sat on almost 300 acres, all valuable. The land was simply too pricey for it to continue as golf. To their credit, Bennell and his Tam O’Shanter team came up with a synergy-rich plan full of solid partners.

Following extensive and occasionally contentious re-zoning hearings and votes from both township officials and the public, a deal to benefit virtually everybody was cemented, particularly Jackson Township locals. The county parks system purchased 205 acres, with the intent to transition the golf canvas into open space preservation, a.k.a., passive parkland recreation area (mostly hiking and biking trails). Bennell’s group closed on Phase 1 of the county purchase in December 2018, with Phase 2 expected to conclude in late summer 2019. Tam O’Shanter donated another 20 acres to Jackson Township for use as soccer fields. The township has already named the facility Tam O’Shanter Park, keeping the course’s legacy alive, and has sought to purchase an additional twenty acres from the county for more sports fields.

The sale and closure of Tam O’Shanter was an exit strategy for the course’s ownership. (Photo: CantonRep.com / Julie Vennitti)

Understandably, with real estate this precious, there is a commercial element to the metamorphosis as well. Medina, Ohio-based ABC Development, LLC, is under contract to purchase 62 acres intended for retail and residential use. Fortunately, whether condos or a big box store emerge, the developer is working with the county and the township to integrate green development, including biking and hiking trails, through everything, including the shopping center. “They (ABC Development) aren’t naïve,” says Bennell. “They know that by doing the right thing, it helps families feel good about the place.”

Why ASU Closed its Course

While the Tam O’Shanter example is somewhat unique, there are plenty of positive golf re-purposing stories across the country.

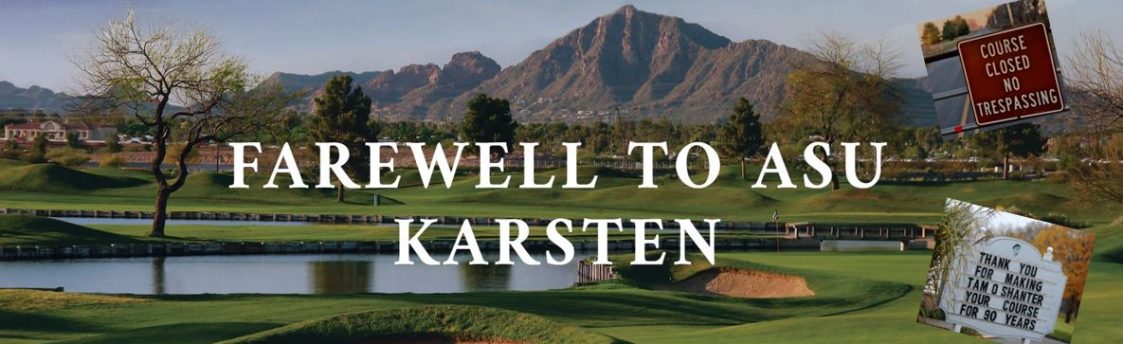

On May 5, the Karsten Golf Course at Arizona State University in Tempe closed for good. Named for chief benefactor Karsten Solheim of PING fame, this 1989 Pete Dye design opened by welcoming an underclassman named Phil Mickelson, who would add two NCAA Championship individual titles to the one he captured earlier that year with the Sun Devils. In its first ten years, it was home to men’s and women’s teams that combined to garner eight NCAA team championships.

The Pete Dye-designed Karsten Course at Arizona State has closed to give way to more university projects, including sports fields.

“At the time, the golf course and those who made it happen really set the standard for the type of collegiate golf facilities needed to recruit and compete for championships,” said Derek Crawford, ASU Karsten’s Director of Golf. “It was a huge success. And it wasn’t just collegiate players who enjoyed the golf course. I would estimate it logged more than one million rounds of public golf during the 30-year span.”

The university’s need to expand its footprint spelled the end for ASU Karsten. Immediate future development will include multi-purpose athletic fields for student and athletic use that will consume what had been holes 1 through 4. Long-term plans identify football, baseball, tennis and track facilities as potential occupants for the old spread.

With the move rumored for as many as eight years, the ASU teams transferred golf operations to nearby Papago Golf Course, a strong, scenic, municipal layout. Upgrades are ongoing, thanks to a private/public partnership between Arizona State University, the City of Phoenix and the Arizona Golf Community Foundation, notably a state-of-the-art practice facility crafted by Mickelson and his lead designer, fellow Sun Devil alum Mike Angus.

High Pointe was Tom Doak’s first solo design. (Photo: Renaissance Golf)

As for Tom Doak’s High Pointe? The 580-acre plot transitioned into a commercial hops farm in 2015 for use in craft beer production.

Doak isn’t alone among outstanding modern architects to see early masterpieces re-purposed into a positive—for some. Bill Coore and Ben Crenshaw, David McLay Kidd and Gil Hanse have all witnessed finished or partly finished courses vanish into the ether.

Most remunerative is likely Hanse’s Tallgrass on Long Island, 60 miles east of Manhattan. It shuttered at age 17 in 2017, yielding to a 127-acre solar farm. Shoreham Solar Commons is expected to generate up to $900,000 in annual tax revenue, displace 29,000 tons of greenhouse gas emissions per year and create almost one million megawatt-hours of clean, renewable energy during its life span.

The site of Gil Hanse’s former Tallgrass golf course on Long Island. (Google Maps)

When golf courses disappear, their individual personality and the communities they fostered are lost as well. But it’s undeniable that some closures are anything but failures.

Case in point is Tam O’Shanter, where Bennell summed up his exit strategy: “A lot of folks who wished it had stayed a golf course have made it a point to say privately, ‘We understand what you’re doing. It’s the best we could have hoped for and we sure like it better than 400 cheap houses. You could have flipped the land to somebody who put up something we hate.’”