Author|Bill Harvey

Source: www.mediavillage.com, August 2021

As the quality of ad attentiveness becomes more important to advertisers, it’s worth delving into the science a bit more, and the place to go for science in our industry is the Advertising Research Foundation (ARF). ARF Executive Vice President Research Horst Stipp had come out of a brilliant career at NBC where he had studied ad attentiveness for years. But then in 2018 he became especially interested in the subject and performed a meta-analysis of dozens of studies. He presented his conclusions in a paper in the Journal of Advertising Research in which he concluded that there are two specific media strategies that agencies and advertisers can use to gain more attention for their ads.

The first strategy is to find environments (programs, websites, magazines, etc.) that have high attentiveness in themselves. In television, for example, it has been known for 60 years that high-rated programs tend to garner more attention from their viewers than lower-rated programs. (At the time this was first discovered, “high rating” meant “above 18.0” and today it means “above 1.5”.)

That’s the main reason why high rated programs charge and get a higher CPM. Another important reason is the prestige value to the retail channels the brand uses to stockholders and to the families of employees.

Some typical types of high-rated programs are sports, primetime and broadcast, although that is too broad a generalization for best results, as attentiveness varies by program.

Highly correlated with high ratings is the emotional sentiment of liking. Programs considered “One Of My Favorites” get higher ratings and higher attention. The liking causes the ratings and the attention. Sixty years ago, some agencies used TVQ scores as a media impact weight to justify buying higher CPM programs based upon “CPM Impact.”

Note that this first strategy, “High Attention Environment,” works independently of the specific creative execution. Its attention effects work on all creative. The great thing about this strategy is that it does work. The rub is that using this strategy tends to increase CPM, which reduces the number of impressions, so that you get more attention but from fewer people per day.

The second strategy also works, and it turns out to be CPM neutral. Horst calls this second strategy “Alignment.” Former ARF CEO Jim Spaeth calls it “Emotional Congruence” and former head of research at Turner Howard Shimmel calls it “Resonance.” What it signifies is that the specific creative execution has some special similarity to the environment. For example, a funny ad works better in a funny show.

Kwon et al in another Journal of Advertising Research paper meta-analyzed 70 studies of alignment, consistently finding about 15% more ad recall and other such communications measures. Each study had its own content codes by which to determine the degree of alignment between an ad and a program, e.g., happy-sad, funny-serious, etc. Typically, in such studies only one univariate dimension was used to classify the ads and the programs.

Unlike the first strategy, the alignment strategy is not creative-independent. Alignment is in relation to the specific creative execution. Because this way of looking at things was not considered historically in the pricing of media — in fact, with so many different creative executions, changing all the time, how could it ever have been factored into media pricing — the alignment strategy is CPM neutral.

Howard Shimmel was the first person to see the application of DriverTags to the alignment strategy. Howard was head of research at Turner at the time (2018). RMT DriverTags (Reset Digital offers them in its Neurocognitive Programmatic product) are the 265 psychological dimensions my 1990s company Next Century Media had discovered drive and explain 76% of all TV program choices. Howard postulated that comparing multivariate dimensions instead of one univariate dimension in executing an alignment strategy ought to work even better, raising attentiveness and ad recall and perhaps persuasion and even sales effect.

Sponsoring a test of his idea, Nielsen NCS found that alignment using DriverTags raises sales effect more than 20% — a lot better than raising mere ad recall 15%. 605 a year later with a large survey of 23,000 people replicated the findings using branding metrics, revealing a 62% increase in first brand mention and a lift of 37% in purchase intent. So, alignment is a valuable attention strategy because it works and it is CPM neutral.

Jumping back to the first strategy, because digital is a very different medium from television (except for premium digital video, attention is a special problem in digital, as users are more ad-avoidant in digital), today there are CPM-neutral ways of finding higher attention environments in digital. This is because there are variables which can be discovered by years of practice that impede and lower attentiveness, and one can detect these in the milliseconds available before a programmatic bid has to be made. The company leading this charge is Adelaide, a spinoff from Parsec, a programmatic company that charged by viewing seconds, and so had an economic incentive to root out the fingerprints of high vs. low attentiveness.

I recommend that CMOs mandate the use of both attention strategies, and contractually set whatever bounds they like regarding CPM impact. Together these strategies will reliably increase sales and branding effect by high double digits, sometimes by 2X or more. And they can do that with no penalty in terms of media price. Or by whatever increase in CPM you authorize. The effects are almost always over 20%, so willingness to pay premiums of up to 10% will still yield gains of at least 10% for the brand.

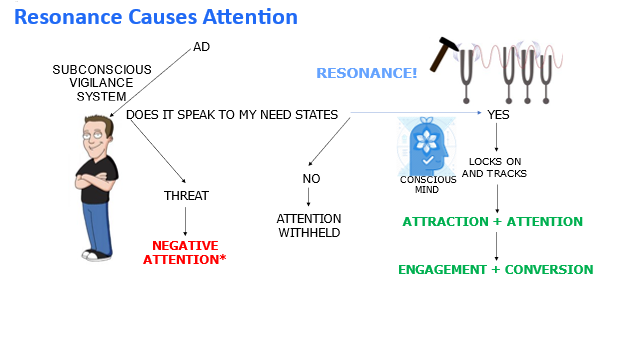

Why does alignment increase attentiveness? There are several “agencies” that cause this effect. One is priming: subsequent information is more quickly processed in the brain to the degree that it is consistent with previous information. A second is mood: we all know that an ad can easily break the mood that the program has created. But what if the ad conveys the same mood as the program? Then the audience flows into the commercial without a sense of dissonance. A third and perhaps the strongest is subconscious relevance to one’s motivations and need states. If the environment on a subconscious level is about leadership and creativity and then the ad at a subconscious level is also about leadership and creativity, there will be attention, engagement and motivation (see slide below). More on the latter subject here.

One will tend to watch programs and read magazines and websites that are relevant to one’s subconscious motivations and need states. So, finding vehicles which are in line with the motivations and need states subconsciously conveyed by one’s ad will produce alignment.

Alignment is one of the subjects which will be heavily researched by a large group of advertisers, agencies and media organized by the 4As and Reset Digital in the Universal Inclusion initiative. The aim of the initiative is to discover how to include everyone in advertising in the ways they want to be included.

An arms race is the predictable outcome of applying new sciences to advertising. The brands who use science first will gain at the expense of those who take longer to adopt science.

Media as a component of advertising and marketing has tended to be undervalued as a commodity ever since Sam Wyman and others began the practice of creating or splitting off media agencies from full-service agencies. Price was the only consideration, and this encouraged C-suites and CMOs to consider media something without an outcome-relevant quality dimension, therefore not worthy of their personal attention.

Media quality is a reality and it directly affects brand growth and the bottom line, stock prices, C-suite bonuses, the CMO’s continued personal success and the longevity of the agency relationship.