Andrew Hutchinson

Source: www.socialmediatoday.com, March 2024

If you’re a regular reader of Social Media Today, you’re no doubt aware of the shift away from in-stream social media sharing, and towards engagement within enclosed message groups instead. All social platforms have seen a decline in personal posting, which could be due to concerns about social posts coming back to haunt you at a later stage, or could be a result of people trying to avoid angst and argument in-stream, or both.

But whatever the reason, the trend is clear: Social media apps are gradually becoming more valued as entertainment sources, while actual interaction shifts to smaller, enclosed chats and communities.

That’s a key trend to note for anyone trying to understand how media engagement works, and where people are more active. But it’s also interesting to reflect on this in relation to social platform metrics, and what we’re actually being told by the different stats and insights.

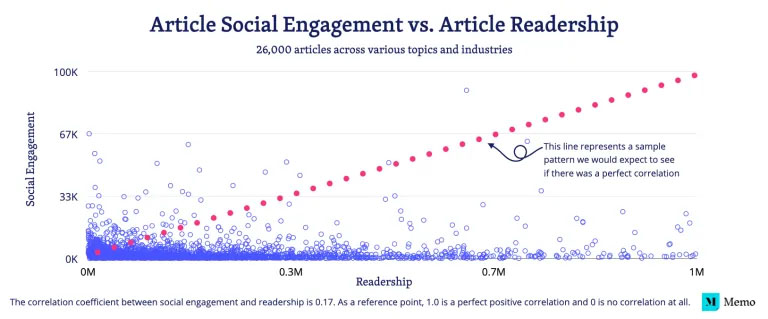

Case in point: This week, the team from earned media insights platform Memo have published a new report which looks at how social media engagement relates to content readership, and whether more social media shares and comments leads to more people actually clicking through to read your posts.

The key finding?

“Across all the articles and topics we analyzed, we found no clear connection between social engagement and actual readers of the news.”

As you can see in this graph, there’s no direct link between how much engagement a post gets in social apps and how many people then read it. Which underlines what you probably already knew, that most people commenting online aren’t necessarily reading the post, but are often just reacting to the headline, while efforts to increase post reach, through more engagement, also may not lead to more people visiting your actual content.

Which, ideally, would be the correlation you would hope for, in that enhanced social media interaction would then see the respective system algorithms amplifying your posts, which would then increase the chances of people clicking through to read it. Memo’s data shows that this isn’t the case, with no definitive link between the two actions.

Does that mean that social media is useless for websites looking to drive traffic?

Well, no, as the brand awareness benefits would still be significant, while there would still be some correlation between exposure and link clicks, even if it is more minor than expected. But the data does suggest that the connection between post reach and CTR is not as direct as you might hope.

Though there is that secondary element, in that while fewer people are engaging with content in-stream, more are now sharing links in message threads. That would be the other data point that would add more context, in understanding whether more links are being shared and clicked on Messenger and WhatsApp, and whether that number is increasing over time.

I mean, given the overall stats for web publications (traffic for all news publishers was down by around 20% on average last year), I would assume that’s not happening either, but it would provide some more color to these notes.

Another element that the Memo analyzed was sentiment, and whether positive or negative stories generate more engagement in social apps.

You won’t believe the results:

“Despite there being more positive coverage in our article sample, social engagement was higher per article among negative articles.”

Wow, what a surprise, posts that have a more negative than positive tilt generate more engagement online.

Which is the core of the problem with the current incentives of digital media, in that you’re going to get far more attention for saying something controversial than you are by providing balanced, unbiased reporting.

That then motivates the worst actors to adopt personas in order to align with this. You see this with sports media all the time, with commentators sharing the most illogical takes in order to spark subsequent debate, and get themselves more attention.

That’s now, unfortunately, filtered into politics as well, with partisan, sports commentator like perspectives driving more benefit in the social media age. Which is how populist politicians are able to gain so much traction, because they look to summarize incredibly complex political issues into simple, meme-style takes, quotes that can then be pasted over an image, and re-shared en masse.

The problem is, nothing is that simple. Yet, that’s what people want, good versus bad, right versus wrong.

Saying that one side of a conflict is in the right may, in itself, feel righteous, but understanding the full complexity of what’s led to that situation requires far more patience, nuance and understanding.

No one’s got time for that, so you end up with argument, and in that scenario, it’s not about who’s more informed or more thoughtful. It’s about right and wrong, based on whatever each person taking part chooses to believe.

And given the engagement that comes with negative content, you can also see how these simplified takes gain traction online.

It’s a fractured information ecosystem, which enables people to pick and choose what they want to believe, though the more logical majority, in most cases, still wins out when it comes to actual action and response.

In most cases. It’s still a concerning trend, but it’s also hard to see how it can be reversed in the current scenario.

So while the data here likely only backs up what you already suspected, it is worth considering what this means for broader online engagement, and the trends that drive action online.